This talk was given at the GDC 2005, on March 10, 2005, in San Fransisco. Mat's slides can be found here.

Content Management for Halo 2 and Beyond

Matthew Noguchi, Bungie Studios

Abstract

Creating an immersive gameplay environment requires more than utilizing the latest shader technology or implementing cutting edge-AI; it requires the content to drive it. As games become bigger and better, content management becomes more and more important. With 12 GB of just in-game assets spread across 39,000 files, we had to build custom tools to effectively handle content management for Halo 2. Even simple concepts like just-in-time editing of game assets or simply loading data from disk turn into complex beasts of implementation at that scale.

Introduction

As games become more and more complex and as hardware limitations have less and less of an impact on the quality of a game, future game innovation will come less from technology and more from content. For the purposes of this paper, content management is the process by which you create, organize and access non-volatile data necessary at runtime to drive a game engine. Content management applies to both runtime usage and persistent storage of game assets. For Halo 2, we were fortunate enough to have a mature persistent object system that handled all our resource management.

The tag system

A tag is the fundamental unit of our resource system. It corresponds to a single file on disk and a C structure in memory. Our tag system is similar to XML; where XML defines data as an XML file and its definition as a schema, we define data as a tag and its definition as a tag_group. However, there are two main differences: XML is stored as text while a tag is a stored as binary data, and an XML schema is defined in a text file while a tag_group is defined in code. We define tag_groups in code using a set of preprocessor macros that break down the corresponding C structure into its component types, e.g. integers, floats, strings.

Example 1: Defining a simple tag

Given the following C structure:

typedef float real;

struct sound_environment

{

real room_intensity_db;

real room_intensity_hf_db;

real room_rolloff_factor;

real decay_time;

real decay_hf_ratio;

real reflections_intensity_db;

real reflections_delay;

real reverb_intensity_db;

real reverb_delay;

real diffusion;

real density;

real hf_reference;

};

We can define the corresponding tag_group in C code as follows:

const unsigned long SOUND_ENVIRONMENT_TAG= 'snde';

TAG_GROUP(

sound_environment,

SOUND_ENVIRONMENT_TAG,

sizeof(sound_environment))

{

{_field_real, "room intensity"},

{_field_real, "room intensity hf"},

{_field_real, "room rolloff (0 to 10)"},

{_field_real, "decay time (.1 to 20)" },

{_field_real, "decay hf ratio (.1 to 2)"},

{_field_real, "reflections intensity:dB[-100,10]"},

{_field_real, "reflections delay (0 to .3):seconds" },

{_field_real, "reverb intensity:dB[-100,20]"},

{_field_real, "reverb delay (0 to .1):seconds"},

{_field_real, "diffusion"},

{_field_real, "density"},

{_field_real, "hf reference(20 to 20,000)},

};

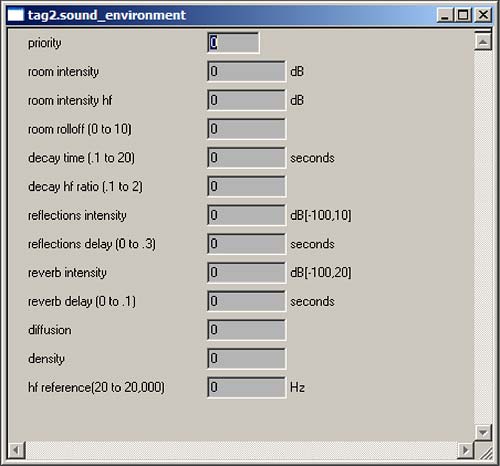

The sound_environment tag_group can then be inspected at runtime; our game asset editor, Guerilla, uses this information to generate a simple editing interface:

To allow for more complex data structures than a simple C struct, we also have a field type called a tag_block. A tag_block is similar to a tag_group; it defines a resizeable array whose elements correspond to a C struct. Since both a tag_group and tag_block can contain any set of fields, including tag_blocks, we can describe almost any type of structured data hierarchy.

Example 2: Defining a more complex tag

C struct definition:

struct s_camera_track_control_point

{

real_vector3d position;

real_quaternion orientation;

};

struct s_camera_track_definition

{

unsigned long flags;

struct tag_block control_points;

};

Tag group definition:

const unsigned long CAMERA_TRACK_DEFINITION_TAG= 'trak';

TAG_BLOCK(

camera_track_control_point_block, k_maximum_number_of_camera_track_control_points, sizeof(s_camera_track_control_point))

{

{_field_real_vector3d, "position"},

{_field_real_quaternion, "orientation"},

{_field_terminator}

};

TAG_GROUP(

camera_track,

CAMERA_TRACK_DEFINITION_TAG,

sizeof(s_camera_track_definition))

{

{_field_block, "control points", &camera_track_control_point_block},

{_field_terminator}

};

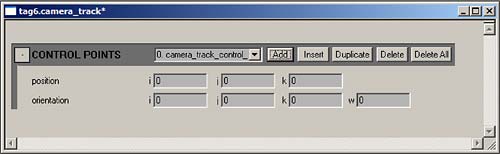

Editing interface:

To access elements of a tag_block, you have to use a macro:

s_camera_track_definition *camera_track= ...;

long control_point_index= ...;

s_camera_track_control_point *control_point=

TAG_BLOCK_GET_ELEMENT(

&camera_track->control_points,

control_point_index,

s_camera_track_control_point);

This is an implementation detail that can easily be abstracted out via more preprocessor macros or through templated wrappers on top of the tag_block structure.

We also have a tag type to allow tags to cross-reference one another, called a tag_reference. A tag_reference is essentially a typed persistent pointer that is maintained by the tag system when a tag is loaded. A tag_reference can be further defined to point to tags of a single tag_group or multiple tag_groups. This simple abstraction is what powers much of our game asset management. For example, if a UI element needs a texture to render correctly, its tag_group would have a tag_reference reference field to a bitmap tag instead of embedding a bitmap directly.

Example 3: Defining a tag that depends on other tags

C struct:

struct item_permutation_definition

{

real weight;

struct tag_reference item;

string_id variant_name;

};

struct item_collection_definition

{

struct tag_block permutations;

short spawn_time;

short pad;

};

Tag group definition:

extern const unsigned long ITEM_DEFINITION_TAG;

TAG_REFERENCE_DEFINITION(

global_item_reference,

ITEM_DEFINITION_TAG);

#define MAXIMUM_NUMBER_OF_PERMUTATIONS_PER_ITEM_GROUP 32

#define MAXIMUM_NUMBER_OF_ITEM_GROUPS 128

TAG_BLOCK(

item_permutation,

MAXIMUM_NUMBER_OF_PERMUTATIONS_PER_ITEM_GROUP, sizeof(struct item_permutation_definition))

{

{_field_real, "weight "},

{_field_tag_reference, "item ", &global_item_reference},

{_field_string_id, "variant name"},

{_field_terminator}

};

TAG_GROUP(

item_collection,

ITEM_COLLECTION_DEFINITION_TAG,

sizeof(struct item_collection_definition))

{

{_field_block, "item permutations", &item_permutation},

{_field_short_integer, "spawn time (in seconds, 0 = default)"},

FIELD_PAD(1 * sizeof(short)),

{_field_terminator}

};

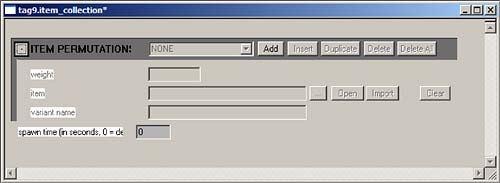

Editing interface:

Both tag_blocks and tag_groups can also have load-time processing behavior defined in code, e.g., to optimize data structures or initialize runtime variables. We refer to this load-time processing as postprocessing. For example, our sound effect tag generates different C structs at runtime depending on the type of sound effect; a distortion effect would take the high-level distortion parameters to create the DirectSound distortion parameters and store that data in the tag. Our shader system has a similar mechanism to take a high level shader definition and optimize it into a more code and hardware friendly format at runtime.

All this manual maintenance of the tag system may seem like a lot of tedious work, but it gives us the benefits one would normally get with a native reflection system. We can write code that analyzes or transforms any tag in a generic fashion. Many operations that can be defined at a high level using type-agnostic pseudocode can be implemented in about the same amount of C/C++ code that manipulates the tag system.

One obvious application of the tag system is the ability to serialize a tag from memory to disk as well as restore a tag in memory from the disk without having to write custom code for each particular asset type; loading a tag is a fairly straightforward process:

- Find the tag_group corresponding to the tag we wish to load

- Load the tag into memory

- Walk the tag hierarchy and postprocess each tag_block element using a post-order traversal

- Walk the tag hierarchy again and for each tag_reference find or load the corresponding tag (starting at step 1)

- Postprocess the tag using the postprocess function defined its tag_group

This load process ensures that once a tag is loaded, it has every tag it depends on also loaded. This process also allows for tags that are multiply referenced to be loaded once at runtime. We can also provide default tags for tag_references that point to non-existent tags. For example, we have a default object tag that is a horribly textured sphere; should any tag reference a non-existent object tag, we show the ball instead.

The payoff[s]

Our tags system as a persistent object system helped us tremendously in the development of Halo 1 and 2.

Level loading process

With most of our game assets defined as tags, none of our leaf game systems (e.g., physics, sound, rendering, AI) manage their respective assets; all resources are handled by the tag system. To facilitate this separation of control between the game and the tag system, we only explicitly load two tags: the globals tag and a scenario tag. The scenario tag is basically the level representation. The globals and scenario tags are available for any game system to access, so for a game system to have access to a particular tag, it must be accessible through the globals tag or the scenario tag.

This consistent loading behavior across the entire game provided us a single entry point for loading a level for gameplay, lightmapping, optimizing for a DVD build, or any other process we wish to apply to an entire level. However, because the only supported way to run the game requires a level to load, it has been very difficult for us to develop interactive tools for viewing and editing data that doesn't need a level loaded, e.g., interactively editing particle effects or viewing animations. What usually happened is that we added scripting commands in the game engine to manually load a given tag and use the automatic reloads to update it on the fly.

Automatic reloading of single tags

Since we only allow access to tag data through handles provided by the tag system, a tag can be reloaded or modified at any time during the lifetime of a game quickly and easily, without adversely affecting other game systems. To make this system more robust, we have a single entry point for reloading tags in case we have a need to have custom cleanup or initialization code when a tag reloads. For example, we pushed data from tags into Havok, a third party physics system. Any time we reloaded a physics tag we had to release all references Havok had on the tag before unloading it from memory, and re-associate those references once the tag was fully reloaded.

For our PC builds, we can easily detect file changes using the file system change notification system. For our Xbox builds, the process is a little more complicated. Our Xbox build cannot use the same file paths as our PC build for performance reasons related to the Xbox's simplified file system. In order to accommodate this restriction, we encode tag paths into a number and generate a directory and filename based on that number. We store this information for all tags on the Xbox in a giant file called the tag file index and use that mapping at runtime to locate tags based on their full path. We use that information every time we synchronize tags from the PC to the Xbox so that we only need to copy the tags that have changed. We call this synchronization process xsync. If the game is running on the Xbox during an xsync, it can detect when the index file updates and reload those tags that have changed in the process. Xsync is an integral part of our content pipeline; artists and designers can changes made on the PC quickly on the Xbox, allowing for quick iteration times on content presented as close to the final presentation as possible. For example, an artist can update the textures on a model on the Xbox as s/he edits them on the PC; for them, the average turnaround time to see a texture update is about 5 seconds.

Cache files: Optimized resources for the Xbox

One powerful aspect of our tag system is the complete separation between resource runtime access and resource storage. Accessing tag data must be done through the tag system; as such, the tag system can provide that data through any arbitrary mechanism: caching the data in memory, generating it at runtime, streaming it over the network, etc. As such, we can completely change the underlying implementation of the tag system without affecting any other game system that relies on the tag system. The fact that our editing build runs from multiple single files is an implementation detail; it is not a necessary component of the tag system itself.

Our single file based tag system is great for editing the game, but to run on retail Xboxes we need to optimize the resource format so that it loads quickly with a minimal amount of memory; loading from multiple single files would clearly have a lot of runtime overhead, as well as rebuilding tags from scratch every time we run a new level. Since all tags can be referenced globally by a handle, once we load a level we have all the assets we needed to load it again. And, because we have the tag_group layout for every loaded tag, we know how to serialize each tag to a fixed runtime address without having to write custom code. When we build the final resource file, which we call a cache file, we simply dump all loaded tags into a giant buffer and write that out to a single file. At runtime, we just need to read that file into a fixed address before we start the level; all other runtime systems behave the same. We do have a few custom steps for stripping out and storing demand loaded data (namely textures and sound), but the overall amount of work to implement the shipping resource files is extremely straightforward.

Geometry cache (AKA, the "anything" cache)

For Halo 2, we decided to add geometry as a cacheable data type. This wasn't nearly as easy to do compared to texture or sound data because we had two different geometry formats, both of which were more complex than just a chunk of data. In order to correctly page in this kind of data, we put the geometry data into a tag_block and inspected its structure to serialize it similar to how we serialize cache files. At runtime, we would inspect the tag_block structure to restore the data properly. This kind of caching mechanism for geometry allowed us to put much more variety of models and environments into every level. It wasn't a perfect caching mechanism, as we did end up with many levels that had too much data to put into memory at once. But in the end, it gave us the flexibility to build much more detailed and diverse worlds compared to Halo 1.

Incidentally, because the geometry cache operated on single-element tag_blocks and not just geometry specific data, we were also able to cache our lip-sync data for combat dialogue using the same system.Tag dependency database

During the course of Halo 2's development, we found the need to analyze the relationships between tags, e.g., locating dangling tag references, finding what tags reference a given tag, etc. In order to analyze these relationships, we loaded every tag and stored all its tag_references. After doing this for every tag, we would then go back and create a graph with a link for each tag to the tags that reference it.

This dependency database also gave us enough information to move entire tag hierarchies around without breaking external references; given a set of tags and the location to move them to, we could determine what tags needed to have their references fixed up and move the tags safely without breaking dependencies. We also used the same information to clone entire tag hierarchies; this let us take existing content and replicate it into its own self-contained hierarchy for further modification without affecting the pre-existing content.

These are a few of the many powerful analysis tools available once you have a type inspection system that is programmatically accessible for your game assets.

Problems with the tag system

Unfortunately, we ran into several problems with our tag system over the lifetime of Halo's development.

Data coupling require more complex reload behavior

As we evolved existing systems, we had tags depend on data in their child tags at runtime, e.g., a sound effect would depend on data in a sound_effect_template tag; changing the child tag would have to trigger a reload of the parent as well in order to maintain a valid runtime state. This was easily solved by generating a mapping from child tags to parent tags; the hard part was determining which child<->parent tag relationships to map. Mapping the dependencies based solely on the tag_group layout wasn't an option for two reasons: many tags did not have their runtime behavior defined from data in child tags, or they had behavior defined by data in a child tag of a child tag. Our solution was a bit more elegant: every time we postprocess a tag, we log which tags are accessed via the global handle system, and store that as the dependency. At tag reload time, we took the list of tags to reload, added the tags that depended on them at runtime, and then reloaded them in the appropriate order.

Unfortunately, the code-driven dependency database caused some strange runtime behavior. Many tags were validated at runtime during the postprocessing of a more global tag. In one particularly horrible case, the shaders attached to our level geometry were validated at postprocess time for level geometry. This had the unfortunate side effect of reloading the level geometry when a bitmap attached to a shader attached to the level geometry changed. Reloading level geometry takes a while because of how it globally affects the game, so even simple bitmap changes could take a few minutes to reload. In order to break these kinds of unnecessary dependencies, we had to manually suppress the dependency mapping process in the postprocess function as they were discovered. As you can expect, this manual process was extremely brittle, and it caused a lot of frustration as the code evolved and created new unexpected dependencies between tags.

More complex tags break Windows

Our basic game asset editor, Guerilla, is a powerful editing tool that uses the tag_group layout to create a simple editing interface for tags. Guerilla iterates over the tag_group fields and generates the editing interface by compositing pre-defined dialogs together to create a form view. Unfortunately, creating dialogs allocates space out of the Windows desktop heap. Since every GUI application uses the desktop heap, exhausting it will cause problems with every GUI application. As our tags became bigger and more complex, Guerilla would often exhaust the desktop heap. This usually manifested in broken behavior across all applications: error dialogs would not display, chat programs wouldn't run correctly, 3d Studio Max would mysteriously eat input without displaying the correct editing dialogs. Our solution, which is more accurately described as a kludge, was to hide fields that only programmers needed to view. This wasn't really a solution; it merely delayed Guerilla's ultimate destruction of Windows.

Tag system destroys the Xbox file system

For our Xbox editing build to run with the new geometry cache system, we had to dump the stripped geometry into a giant monolithic file. Our first pass at this process had us strip the geometry and other cacheable data at load time on the Xbox. At first, this solution worked pretty well. Cacheable data was stripped at load time, resulting in a smaller memory footprint, and our editing build only had to access a single file to page in cacheable data. However, this resulted in an explosion of load times later on in the project as we added a ton of sound assets. Sound assets by far dwarf every other kind of asset we have, in terms of variety and sheer size. We spent more time writing out cacheable sound data than we did reading in tags. To reduce load times, we moved the cacheable data stripping into the xsync process. This increased xsync times a lot, but it reduced Xbox load times enough to make it a net win in terms of overall time wasted waiting to run the game. We did run into a few runtime consistency problems, as the xsync process wasn't completely transactional. You could occasionally have a tag loaded at runtime that failed to cache its data properly at a later xsync time making the tag basically have no valid cacheable data. However, this was due to space constraints on the Xbox and is something that is easily solvable in the future.

Combat dialogue destroys the Windows file system

The combat dialogue data we had for Halo 2 was one of the most horrific data sets we could have ever created for any game for three major reasons:

- The order of magnitude increase in complexity with our combat dialog system required an equal increase in quantity of combat dialogue sounds.

- To ease our localization process, spoken dialog had multiple language versions embedded in a single sound tag.

- Raw sound data and tag data were interleaved throughout the sound tag.

These three factors caused the Windows file system to break when we added combat dialogue for all the major characters. Running a level now required us to read in a relatively small amount of data over thousands of files with a non-predictable access pattern. This kind of interaction with the file system managed to thrash the file system cache every time we loaded a level that had characters with combat dialogue, which inconveniently happened to be every single campaign level.

Thrashing the Windows file system cache is one of the most effective ways to de-optimize any file system activity; any file system data that could be read from memory now has to come from the disk, which is obviously an order of magnitude slower. For us, that caused load times to increase from 15-20 seconds to 5-8 minutes for the more complex campaign levels, even on machines with 2 GB of RAM.

To maintain reasonable load times on the PC, we resorted to shadowing the combat dialogue directory from source control. Obviously, this wasn't the most optimal solution, but short of writing our own PC side file system, it was the best solution we could come up with.

Future considerations

As powerful as our tag system is, it is still cumbersome to setup new tag_groups and tag_blocks. A programmer has to manually define a tag in code, a process that is both extremely error prone with those unfamiliar with the system and quite brittle as data formats change and evolve. A more maintainable solution would be to separate the tag_group definition into a separate file and build process; one major benefit of a separate system would be to provide for a less brittle process for defining a tag_group and making sure the layout is consistent with the compiler's struct layout.

Another area rife with possibilities would be to allow for arbitrary data stores to serve as the backend of the tag system. As it stands right now, the tag storage system is basically a database implemented on top of a file system. We can easily abstract out the storage system so that we can load tags from anywhere; a network share, a database that generates the tag on the fly, from a collection of text files, or any other mechanism we come up with.

Conclusion

Our tag system was an integral part of our overall development process that enabled us to effectively develop many different systems for Halo 1 and 2 while at the same time providing a resource management system that could be targeted to widely varying runtime platforms without affecting other code. By creating a cleanly separable persistence system that programmatically provides type inspection, we were able to analyze and optimize our resources quickly and easily with a minimum amount of effort and with very little modification of the underlying system.